What should the role of ecological researchers be in the times of environmental crisis?

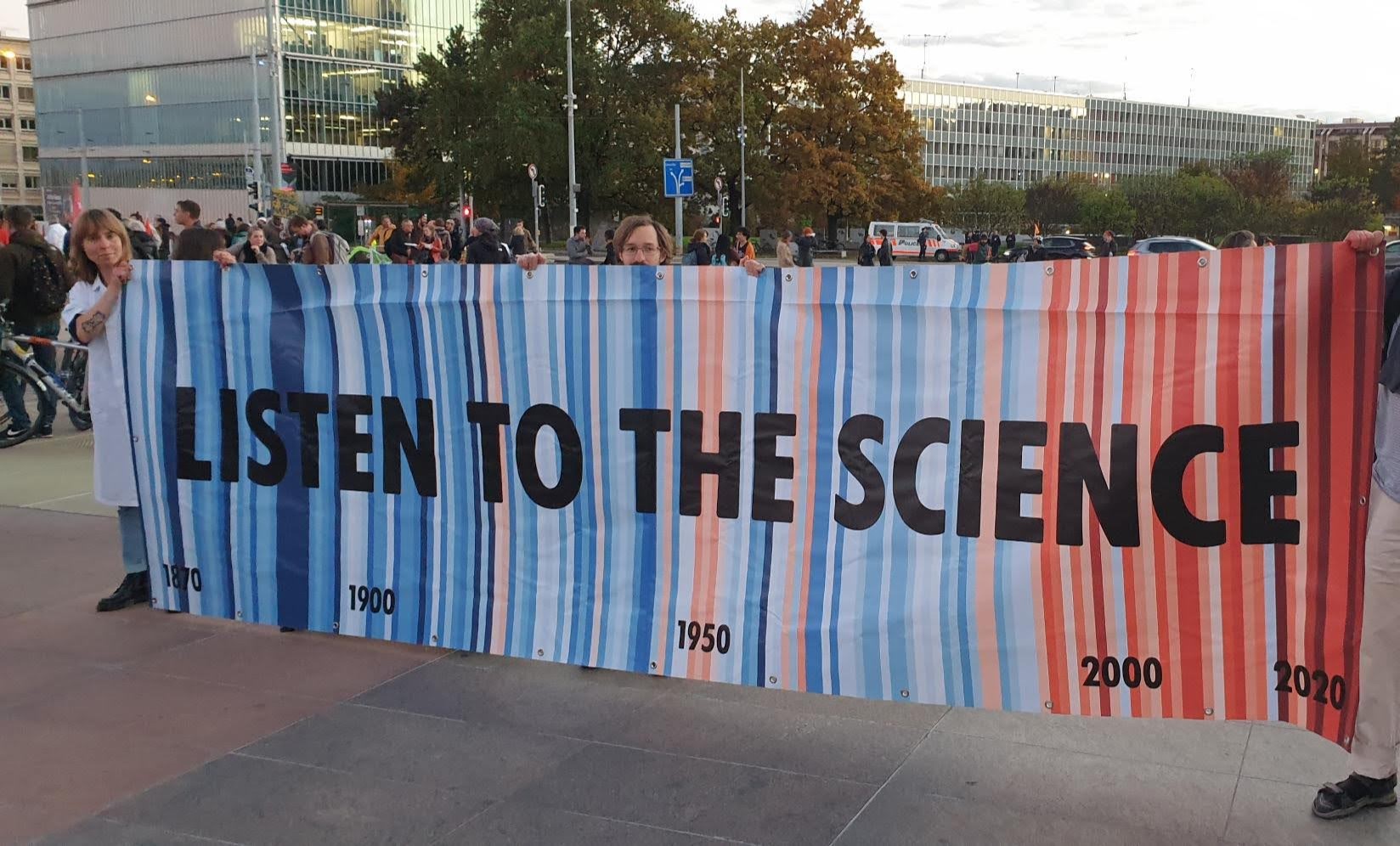

As the climate crisis and loss of biodiversity continue, ecological researchers are faced with a dilemma: are we supposed to continue our research as usual, or does the crisis of nature we witness compel us to speak up and take action? The disappearance of nature is an existential crisis not just to our societies, but also to our profession: we are losing the very target of our study. Do the times of crisis require a redefinition of the role of ecological researcher towards society? If so, what responsibilities come with the different roles we can (and should) take?

I have explored this theme by organizing workshops internationally ("Ecology for a social revolution", "A research career vs campaigning for change – a false dichotomy?") and by giving talks and running workshops locally.

The role of species interactions and local adaptation in determining the range limits of Impatiens glandulifera

Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) was brought to Europe in 1839. Since then, it has spread across the continent from Southern Europe to Northern Scandinavia, replacing native plant communities. How is a species which is restricted to a relatively small geographic area in its native range able to establish and spread successfully across such a wide range of climatic and biotic conditions? I am studying the importance of local adaptation, phenotypic plasticity and enemy release in enabling the species to spread successfully.

Seedling tolerances to heat, drought and frost are correlated across temperate tree species

Most trees die as seedlings, and a large part of this mortality is caused by environmental stress, such as drought or frost. Whether there are trade-offs or positive correlations between tolerances to different climatic stressors can determine species’ survival in the rapidly changing climate. We show how stress tolerance to frost, drought and heat at seedling stage correlates across temperate tree species, but, surprisingly, is not related to the distributions of adult trees. This shows how adult distributions, especially of long-lived species like trees, might not be indicative of the optimal climate for the seedlings.

Read the article in Journal of Ecology, and the related blog post here.

Ecophysiological and morphological traits explain species' responses to climate warming

Being able to predict species’ responses to environmental change is one of the central goals of ecological research. Functional traits have often proved to be successful in this. Nevertheless, what has been often lacking is the understanding of the mechanism behind why a specific trait is related to an environmental gradient or a demographic trend. We show that both morphological and eco-physiological traits are good predictors of alpine plant species’ demographic responses to warming. Nevertheless, only eco-physiological traits explain why certain species can survive in the new climate.

Read the article in Functional Ecology, and the related blog post here.

Community and ecosystem -level effects of insect herbivory in temperate forests

During my PhD I studied how herbivory by caterpillars of Winter moth (Operophtera brumata) affect the gas exchange and chemistry of their host plant, oak (Quercus robur).

Read about the effects of insect herbivory on oak physiology in New Phytologist, and in Plos One. This paper in Ecology describes the effects of early-season herbivory on the late-season insect community on oaks. And in this recent paper I estimate the effects of insect herbivory on the carbon cycle of a temperate forest.

The role of the wolf spider Pardosa glacialis in an Arctic food web

Trophic cascades are expected to be common in simple food webs, such as in the Arctic. We tested this by manipulating the abundance of the wolf spider Pardosa glacialis, the top predator of the arthropod food web in the Zackenberg valley in Eastern Greenland. No trophic cascade was detected, most likely because the top-down effect of the spider extends from herbivores to detritivores and other spiders.

Read about the study in Basic and Applied Ecology.